As many who read my blogs likely have noticed, I typically focus on events happening in the West Piedmont region as my subject matter, with an occasional departure to a national topic, often having to do with some form of mobility. Today, I would like to share my observations and some of the history of the High Line, a relic of Manhattan’s almost forgotten industrial past, how this once-active form of infrastructure has been repurposed as an outstanding recreational and transportation asset for New York City, and how it serves as a great model for adaptive re-use and historic preservation. I include photos with captions to better articulate some of the features of the High Line.

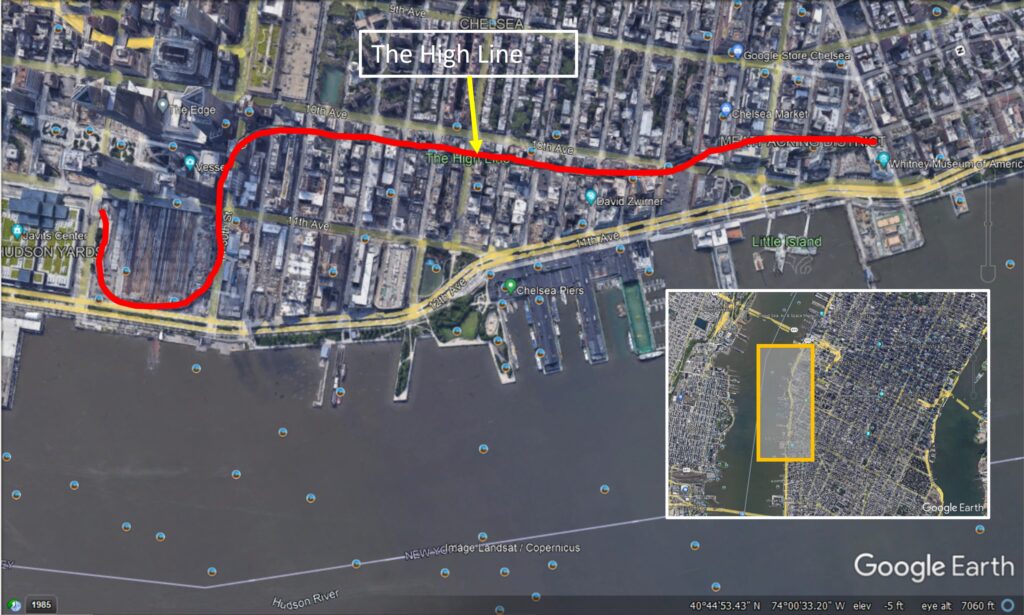

The High Line is a very successful former elevated rail line that sat abandoned, or nearly so, for decades until it was repurposed as a premiere public space and pedestrian greenway. The High Line extends for nearly 1.5 miles, from W 34th Street south to Little West 12th Street/Gansevoort Street, and just a stone’s throw from the Hudson River along much of its length. The map below shows the path of the High Line, and the inset illustrates its location in Manhattan.

This map shows the approximate path of the High Line along Manhattan’s West Side. The inset shows its location relative to Manhattan Island.

Some historical context of the High Line is necessary before I get into the jewel this former elevated railway has become. According to Friends of the High Line, www.thehighline.org, the elevated rail line which came to be known as the High Line was completed and began operation in the 1930s for the purpose of transporting various agricultural food products to southern parts of Manhattan. Prior to its construction, trains operated at street level along 10th Avenue, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of people struck by trains; because of this hazard to human life, 10th Avenue was unofficially known as “Death Avenue.” With the greater prevalence of trucking during the second half of the 20th century, however, the High Line began to fade into obsolescence, so that by the 1980s rail operations had ceased completely. In the early 1980s, efforts to preserve the defunct structure began with the founding of the West Side Rail Development Foundation, aided by federal legislation (the Trail System Act) which made it easier for former rail lines to be converted into recreational assets. For years the threat of demolition loomed large, as nature began to take root, literally, in the form of wild plants and weeds growing on the deck of the structure. However, under the Bloomberg administration which supported the repurposing of the High Line as a recreational asset, the first phase of the linear park came to fruition in 2009.[1]

Today, the High Line is a thriving recreational attraction on Manhattan’s West Side, serving as both a sanctuary from the hustle and bustle of the city below, and a place to view this city from a unique perspective – either for direct observation or for myriad photographic vantage points. What’s more, a sense of authenticity abounds, as the design incorporates many of the characteristics of the High Line while it was in operation. The observer will notice that, in many places, the pathway was designed to resemble wooden planks with breaks in it that allow for vegetation (to resemble weeds) peeking up in between, as well as around remnants of track left in place. Along its length are places for sitting, as well as for taking in views of Manhattan’s many streetscapes. In some areas, the rail line passed under or through buildings, which provides yet another unique perspective. One may access the High Line from staircases or elevators at street level from numerous locations along its length.

This image of the High Line shows how it fits neatly into Manhattan’s urban context, surrounded very closely by myriad residential towers.

The High Line is much more than a recreational asset, though. For visitors and residents alike, it serves the purpose of a pedestrian conveyance in a more tranquil setting than one would encounter at street level, where traffic must always be cautiously observed while streets and avenues are crossed. In addition to the features that lend themselves to the authenticity of the experience such as plants designed to look like weeds and the elevated views of the streets below, every turn reveals yet another building, many of them condos or apartments, or one of several murals. The many people walking along the structure is indicative of its success. To learn more about the history of the High Line as well as its features, please visit https://www.thehighline.org/.

This image shows the popularity of the High Line, owing to the vast number of people walking along its deck. Intentionally-placed vegetation gives the appearance of weeds and wild plants growing through a once-abandoned railway. Another observation is the vast number of residential buildings abutting the structure, which is a testament to the popularity of such community assets.

This image shows a stairway access point to street level, seating areas, remnants of a railroad track, and intentionally-placed vegetation to resemble that which at one time flourished on the abandoned deck.

In our area, we see less dramatic, yet significant variations of the High Line. Some examples that come to mind are the Danville Riverwalk Trail in Danville, the Dick & Willie Passage Trail in Martinsville and Henry County, and the Mayo River Rail Trail in Stuart, all of which have replaced or been associated with a railroad to one extent or another. The repurposing of former rail lines, or other uses, to recreational and/or transportation facilities really contributes to the quality of life as well as historic preservation in localities, emphasizing the life and culture of a certain time in a place’s history. In the case of the City of Danville, the Riverwalk Trail not only preserves a railroad right-of-way (Crossing at the Dan), but links two prominent recreational facilities, Dan Daniel Memorial Park and Anglers Park, together. Anytime a facility harkening back to days gone by is redeveloped into a recreational or transportation facility, the community benefits via greater opportunities for physical health betterment through active transportation, greater modal choice in transportation, more recreational opportunities, and historic preservation.

View east along W 23rd Street looking toward 10th Avenue from the High Line. This group taking a selfie shows the popularity of viewing New York City from this unique perspective.

Having grown up in New York City’s borough of the Bronx, I remember the days when my grandfather worked as a carpenter at an interior design production facility on W 23rd Street, and when we went to visit him, I remember seeing the derelict elevated rail line just to the east, never thinking that in years to come it would become the premiere recreational and pedestrian facility it is today and that I would be standing atop of it, looking down to where I once stood as a boy, wondering where it led. That said, “the shop,” as my grandfather used to refer to it, has since been replaced by luxury condos, testifying to the fact that the only constant is change, though the High Line remains a reminder of the industrial past of Manhattan’s West Side, and one that preserves that legacy well.

If you accomplish your commute or other essential trip by walking or biking on the Dick & Willie Passage Trail, the Danville Riverwalk Trail, the Mayo River Rail Trail or any other street or sidewalk in the region, don’t forget to log your trips into the RIDE Solutions app to earn points toward discounts on shopping, dining, services, or entertainment, or for the opportunity to enter a raffle to win a gift card; the latter could be very valuable this time of year! If you don’t yet have the RIDE Solutions app, download it today for free at ridesolutions.org!

[1] High Line – “History.” Friends of the High Line. Copyright 2000 – 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2021. https://www.thehighline.org/history/.